Bear Tracks

Bear Tracks Aspens are beautiful trees–especially their smooth black and cream trunks. And while those trunks serve an important purpose for the tree (see my “other” blog on santafe.com) they are also very attractive to other creatures.

Elk and deer frequently browse young branches and twigs of aspen, but also take bites from somewhat older trunks especially in Winter when other forage is lacking. Young Black bears will climb the trunks under mama’s direction if something threatens. We can be sure of this because each of them leaves marks on the trunks.

Anything which scrapes or scratches the thin bark of aspens results in a very obvious black scar several years later as the tree heals over the damaged spot by growing a protective, corky bark. A scrape from a falling tree, elk teeth or bear claws all show up clearly. And people leave their marks, too.

“Culturally modified tree” is the euphemism for a trunk which has been carved or marked by people. Because they provide a smooth canvas and dramatic results, aspens are often a favored tree for carvers.

Elk and deer frequently browse young branches and twigs of aspen, but also take bites from somewhat older trunks especially in Winter when other forage is lacking. Young Black bears will climb the trunks under mama’s direction if something threatens. We can be sure of this because each of them leaves marks on the trunks.

Anything which scrapes or scratches the thin bark of aspens results in a very obvious black scar several years later as the tree heals over the damaged spot by growing a protective, corky bark. A scrape from a falling tree, elk teeth or bear claws all show up clearly. And people leave their marks, too.

“Culturally modified tree” is the euphemism for a trunk which has been carved or marked by people. Because they provide a smooth canvas and dramatic results, aspens are often a favored tree for carvers.

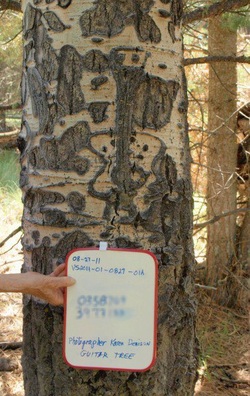

Can you find the guitar?

Can you find the guitar? Earlier this Summer, I was happy to be drafted as part of a team in a multi-year effort to survey and document “dendroglyphs” (tree carvings) within the Valles Caldera National Preserve. Though coordinated by VCNP staff specialist Ana Steffen, the effort is largely manned by volunteers who very thoroughly record the carvings on trees through the Preserve. It’s tedious, painstaking work as each carving is measured, GPS mapped, photographed and then sketched; the latter because sometimes, especially on old carvings, the person standing in front of the tree must feel or peer very closely at the scars to determine if a particular crack or scrape was intentionally made by the carver or was additional casual damage inflicted by elk or aging. Aspen trunks only live 80-100 years so many of the surveyed trees are dead snags and the bark is in bad shape. If you like puzzles, this is a good challenge.

Most dendroglyphs seem to be of the sort where a name and sometimes a date is written. This is common everywhere and I’m sure you’ve seen this. However, on the VCNP is a slice of history recorded on those oldest aspens: near the turn of the last century, shepherds–most speaking Spanish or Basque–were stationed in the high valleys with large flocks throughout the summers. Solitary and with little else to do, many left their marks–literally–on the trees. In addition to names and dates, those men left us little clues about that sort of life.

Names, dates, notes to the girlfriend back home, and drawings are all found on the old trees. The handwriting is often a beautiful, flowing, old-style script which must have been traced with a light touch rather than the deep, coarse block letters seen along many public land trails. And a large percentage of the drawings involve pornographic subjects but again, the stylistic differences between the older and more recent carvings bespeak a period when time was more available.

So although I prefer the unmarred aspens, the urge to speak is a strong one and the medium was once bark or stone, rather than the electronic ether. Watch as you walk for the messages left by all those (human or animal) who have gone before.

Most dendroglyphs seem to be of the sort where a name and sometimes a date is written. This is common everywhere and I’m sure you’ve seen this. However, on the VCNP is a slice of history recorded on those oldest aspens: near the turn of the last century, shepherds–most speaking Spanish or Basque–were stationed in the high valleys with large flocks throughout the summers. Solitary and with little else to do, many left their marks–literally–on the trees. In addition to names and dates, those men left us little clues about that sort of life.

Names, dates, notes to the girlfriend back home, and drawings are all found on the old trees. The handwriting is often a beautiful, flowing, old-style script which must have been traced with a light touch rather than the deep, coarse block letters seen along many public land trails. And a large percentage of the drawings involve pornographic subjects but again, the stylistic differences between the older and more recent carvings bespeak a period when time was more available.

So although I prefer the unmarred aspens, the urge to speak is a strong one and the medium was once bark or stone, rather than the electronic ether. Watch as you walk for the messages left by all those (human or animal) who have gone before.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed